Insights

What’s the future for acute inpatient rehabilitation gyms?

By Iona McAllister

Associate Director Iona McAllister looks forward to a time where hospitals provide better spaces that support health independence and prevention of health decline.

As a registered clinical exercise physiologist and experienced hospital operations manager, Iona has become increasingly disappointed with the status quo of hospital rehabilitation gyms. Most physiotherapists assist patients in corridors, as hospital gyms, if there is one, are usually poorly located and difficult for immobile patients to access.

Iona has been working alongside North Manchester General Hospital physiotherapist Peter Eckersley and Chartered Physiotherapist Rebecca Dunkerley to champion the improvement of rehabilitation gyms in acute hospitals. The trio are among a large number of healthcare professionals who see a clear clinical benefit to improving inpatient gyms.

“Studies show inpatient mobilisation efforts can result in a 37 per cent reduction in falls and 86 per cent fewer pressure ulcers, so there’s a clear motivation for getting this right,” says Iona.

Over the summer the three interviewed clinicians from North Manchester NHS Foundation Trust and based on the insight they gathered, they are now proposing what the future of rehabilitation could look like.

They were struck by the simplicity of a 9-year-old’s response to one of their leading questions.

When asked to re-imagine the new North Manchester General Hospital, Alfie’s ideas were straightforward. Alongside the ideas they would expect a child to dream up: a “boss chill-out room,” a secret stash of chocolate, a worship room, and beds for both adults and children; he dedicated the largest space to a gym.

At first glance, the idea of a hospital gym designed by a child may appear whimsical. Yet Alfie’s vision speaks to something profoundly relevant, the growing expectation among younger generations that movement, mobility, and exercise are not luxuries but core components of health. With better public health education in schools and a culture that increasingly values activity and fitness, tomorrow’s patients will expect hospitals to help them keep moving, even during illness.

The contrast with today’s reality could not be starker. Rehabilitating inpatients in the average UK hospital remains almost impossible. Even the most skilled physiotherapist or occupational therapist is constrained by the environment in which they work: cramped patient rooms, corridors cluttered with equipment, and therapy spaces that are often undersized, overcrowded, or shared with outpatients. Not to mention the distances that need to be covered to access these spaces. These environments not only limit rehabilitation potential but actively undermine recovery.

“If prevention is better than cure, then the prevention of deconditioning in hospital must be seen as a clinical necessity. To achieve this, we must redesign healthcare estates to include dedicated and easily accessed rehabilitation spaces. Mobilisation is medicine and our hospitals must reflect that,” says Iona.

The scale of the problem: immobility in hospitals

Immobility remains a defining feature of the inpatient experience. Evidence shows that hospitalised patients spend up to 87-100 per cent of their time in bed (Fazio et al., 2020). While this statistic is alarming for all patients, it is especially concerning for older and frail adults. Functional decline during admission is common, with this cohort, found to be 61 times more likely to leave hospital with reduced independence compared to younger and more resilient groups (Gill et al., 2004).

The consequences extend beyond physical weakness. Prolonged immobility is linked to longer lengths of stay, increased rates of hospital-acquired infections, falls, pressure injuries, delirium, and higher mortality (Kortebein, 2009). In older and frail adults, ten days of bed rest can equate to a 10 per cent loss of muscle mass and an even greater loss of strength (Kortebein et al., 2008). This is not merely a loss of stamina; it can be the difference between returning home independently and requiring permanent care at great expense.

Hospitalisation, in other words, is itself a risk factor for deconditioning and decline. Too often, patients are discharged later than necessary, not because of ongoing medical need but because of the loss of mobility and function acquired during their stay (Graf, 2006). Almost half of delayed discharges in the UK are linked to deconditioning rather than clinical instability (Lim et.al., 2006).

This is why campaigns such as #EndPJparalysis have gained traction, highlighting the dangers of leaving patients inactive and in pyjamas for long stretches of admission (Oliver, 2017). The campaign reframes mobilisation not as an optional extra but as a form of treatment in its own right.

A gap in the system: therapy without space

Despite this, national design guidance does not currently instruct dedicated inpatient rehabilitation spaces. Health Building Note (HBN) 11-01 sets out expectations for therapy facilities in primary and community care, recommending 64 sqm gyms and 24 sqm activities of daily living (ADL) rooms (NHS England, 2013). However, there is no equivalent provision for inpatient rehabilitation spaces in acute hospitals.

The result is that physiotherapists and occupational therapists often work in makeshift or unsuitable environments:

- Corridors and stairwells for mobility and stair assessments.

- Shared outpatient gyms for inpatient therapy, with access restricted by scheduling clashes or by being too far away.

- Multipurpose rooms for functional assessments, often compromising patient privacy and dignity.

A consistent theme emerging from consultations with allied health professionals (AHPs) is that they feel underrepresented in hospital planning and innovation, despite playing a pivotal role in patient recovery and discharge. Their absence in design conversations translates directly into worse patient outcomes and staff inefficiencies.

By contrast, Australasian Health Facility Guidelines recommend separate inpatient and outpatient therapy areas, including ward-adjacent “satellite therapy units.” These are designed to minimise patient travel, reduce inefficiency, and ensure safe, timely mobilisation (Australasian Health Infrastructure Alliance, 2021).

North Manchester General Hospital tests a new rehab model

Recognising these challenges, a multidisciplinary team at North Manchester General Hospital set out to investigate whether embedding dedicated inpatient rehabilitation spaces aligned to inpatients wards could improve outcomes and operational efficiency.

The team comprised healthcare planners, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, operations specialists, and architects. They collected data across three domains:

- Clinical demand – types and frequency of therapy assessments.

- Operational barriers – time lost due to distance and patient transfers.

- Space requirements – functional and equipment needs for different specialties.

Clinical demand

In a single week, the therapy team recorded the need for dozens of assessments that required specialist space: stair practice, kitchen ADLs, walking capacity, and mobility tests using parallel bars and plinths. Yet many of these could not be delivered due to lack of access. Only one in five patients who might have benefitted from gym-based rehab were able to access it.

Operational barriers

A time-and-motion study revealed that an average rehabilitation session took 110 minutes, largely because AHPs had to walk long distances, find wheelchairs, transfer patients, and wait for lifts. On average, this limited a member of staff to only four patients per day. Locating therapy spaces adjacent to wards shows reduced travel to just five minutes, enabling seven or more sessions per day (See image below).

Space requirements

Workshops with 35 therapists (Figure 2) defined which interventions could be done safely in patient rooms (such as sit-to-stand or bathroom transfers) and which required gym space (stair practice, advanced walking, cardiopulmonary tests, ADL kitchens). They also identified essential equipment: plinths, parallel bars, stairs, exercise bikes, hoists, mock front doors, and kitchenettes.

Designing effective inpatient therapy spaces

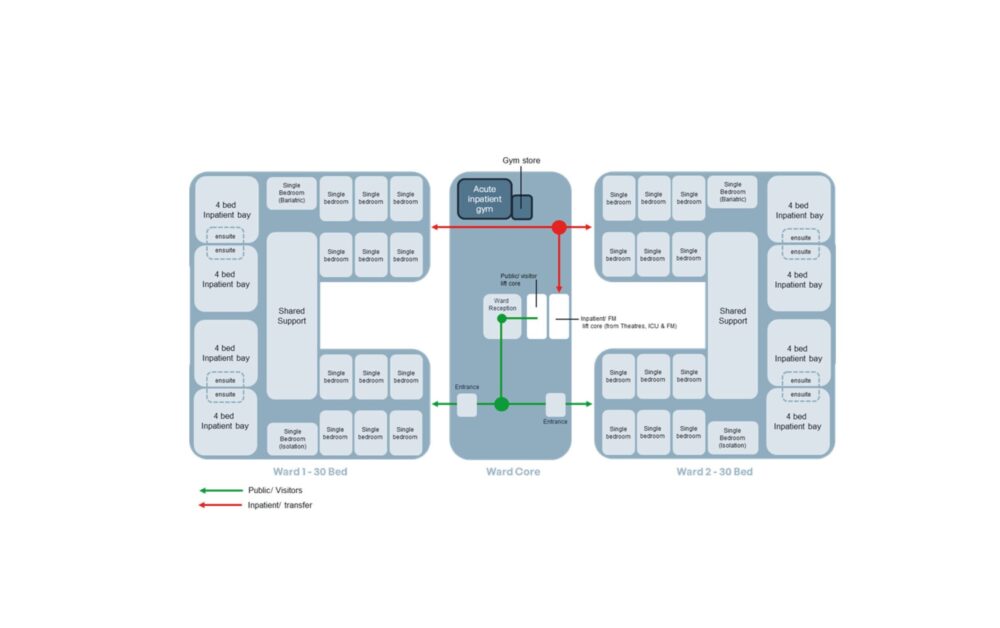

The North Manchester General Hospital team developed a design brief centred on three principles: functionality, flexibility, and dignity. There were no limitations given to the team before they designed the space and are looking at it from a conceptual perspective (See drawing below).

MJ Medical Associate director imagines better rehabilitation spaces for inpatients

Functionality

Each gym was sized at 40 sqm, supported by a 10 sqm equipment store; compact enough to fit within ward cores yet large enough to house essential equipment. The layout supported circuit-based rehabilitation, allowing patients to practise walking, stairs, strength training, and daily living activities.

Flexibility

Spaces were designed to be future-proof. They could be reconfigured for evolving rehab practices or, in times of crisis (e.g., pandemics), converted into standard inpatient accommodation.

Dignity

Therapeutic design features included natural light, calming finishes, wide accessible entrances, and ceiling-mounted hoists to support safe handling. Importantly, the gyms were located adjacent to wards, ensuring patients could move seamlessly between their room and therapy without long transfers.

Extending rehabilitation outdoors

Where estates permitted, adjoining therapy gardens or terraces were included, allowing patients to practise mobility in real-world conditions. Varied walking surfaces, steps, and planting created safe but meaningful challenges, while also supporting mental wellbeing.

Clinical, operational, and workforce benefits

The case for change extends across multiple domains:

- Patient outcomes: Inpatient mobilisation can reduce falls. There is no link between increased mobilisation and falls (Kissane et.al., 2023).

- Operational efficiency: Faster, safer discharges reduce pressure on emergency departments and ambulance handovers. Mobilisation can reduce hospital stays on average by 2.18 days (Cortes, 2019).

- Staff time: Ward-adjacent gyms can double the number of daily assessments available.

- Workforce identity: Visible, functional therapy spaces acknowledge the essential role of AHPs, fostering interprofessional working and collaboration.

There are also opportunities for wider use. Outside of clinical hours, gyms could host patient education groups, safe self-directed exercise for mobile patients, or even staff wellbeing initiatives, aligning with NHS workforce goals.

Prevention is better than cure – the estates perspective

From an estates and planning perspective, embedding acute inpatient gyms is not merely an optional enhancement; it is a direct response to the principle that prevention is better than cure. By preventing deconditioning and functional decline, these spaces reduce avoidable harm, shorten recovery time, and reduce system costs.

The scale of benefit is clear:

- Patients retain independence and avoid long-term care needs.

- Clinicians can deliver more effective, timely rehabilitation.

- Hospitals reduce delays, readmissions, and complaints.

- Preventing complications reduces costs for health and social care by avoiding the need for increased care packages and additional community services.

In short, the estates we build can either perpetuate immobility or enable recovery. The choice is ours.

Conclusion: Mobilisation is medicine

Returning to Alfie’s vision, the hospital with the biggest space reserved for a gym is no fantasy. It is an urgent reminder that the hospitals of the future must not just treat illness but actively support health, independence, and prevention of decline.

Every ten days of immobility can rob an older or frail adult of 10 per cent of their muscle mass. Nearly half of delayed discharges are due to deconditioning, not clinical need. These are not abstract statistics; they represent lives diminished, independence lost, and health systems under pressure.

Embedding therapy spaces in hospital design which reduce travel time for patients is therefore not aspirational, it is essential. Mobilisation is medicine. If prevention is truly better than cure, then keeping patients moving must be a cornerstone of our healthcare estates.

Iona McAllister – Associate Director, MJ Medical

Iona is a registered clinical exercise physiologist and experienced hospital operations manager. She leads on clinical modelling, models of care, schedules of accommodation, and the integration of operational efficiency into healthcare design.

With a proven track record in the delivery of large-scale healthcare facilities, Iona combines her clinical expertise with operational insight to ensure hospitals are safe, effective, and ready from day one. She has played a key role in projects ranging from major regional cardiac centres to input into the development of the New Hospital Programme.

Iona’s experience in operational readiness means she understands how estate design directly impacts patient flow, staff efficiency, and quality of care. As both a clinician and planner, she bridges the gap between frontline healthcare delivery and strategic estates planning.

References

Australasian Health Infrastructure Alliance (2021). Australasian Health Facility Guidelines – B.0140 Allied Health / Therapy Unit. AHIA.

Cortes, O.L., Delgado, S. and Esparza, M., 2019. Systematic review and meta‐analysis of experimental studies: In‐hospital mobilization for patients admitted for medical treatment. Journal of advanced nursing, 75(9), pp.1823-1837.

Fazio, S., Stocking, J., Kuhn, B., Doroy, A., Blackmon, E., Young, H.M. and Adams, J.Y., 2020. How much do hospitalized adults move? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Applied Nursing Research, 51, p.151189.

Gill TM, Allore HG, Holford TR, Guo Z. Hospitalization, restricted activity, and the development of disability among older persons. JAMA. 2004;292:2115–2124.

Graf, C. (2006). Functional decline in hospitalized older adults: it’s often a consequence of hospitalization, but it doesn’t have to be. American Journal of Nursing, 106(1), 58–67.

Kissane, H., Knowles, J., Tanzer, J.R., Laplume, H., Antosh, H., Brady, D. and Cullman, J., 2023. Relationship between mobility and falls in the hospital setting. Journal of Brown Hospital Medicine, 2(3), p.82146.

Kortebein, P., 2009. Rehabilitation for hospital-associated deconditioning. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation, 88(1), pp.66-77.

Kortebein, P., Symons, T.B., Ferrando, A., Paddon-Jones, D., Ronsen, O., Protas, E., Conger, S., Lombeida, J., Wolfe, R. and Evans, W.J., 2008. Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 63(10), pp.1076-1081.

Lim, S.C., Doshi, V., Castasus, B., Lim, J.K.H. and Mamun, K., 2006. Factors causing delay in discharge of elderly patients in an acute care hospital. Annals-Academy of Medicine Singapore, 35(1), p.27.

NHS England (2013). Health Building Note 11-01: Facilities for primary and community care services. London.

Oliver, D., 2017. Fighting pyjama paralysis in hospital wards. BMJ, 357:j2096.